When police knock on doors, it is seldom good news for those inside. I know; I knocked on doors.

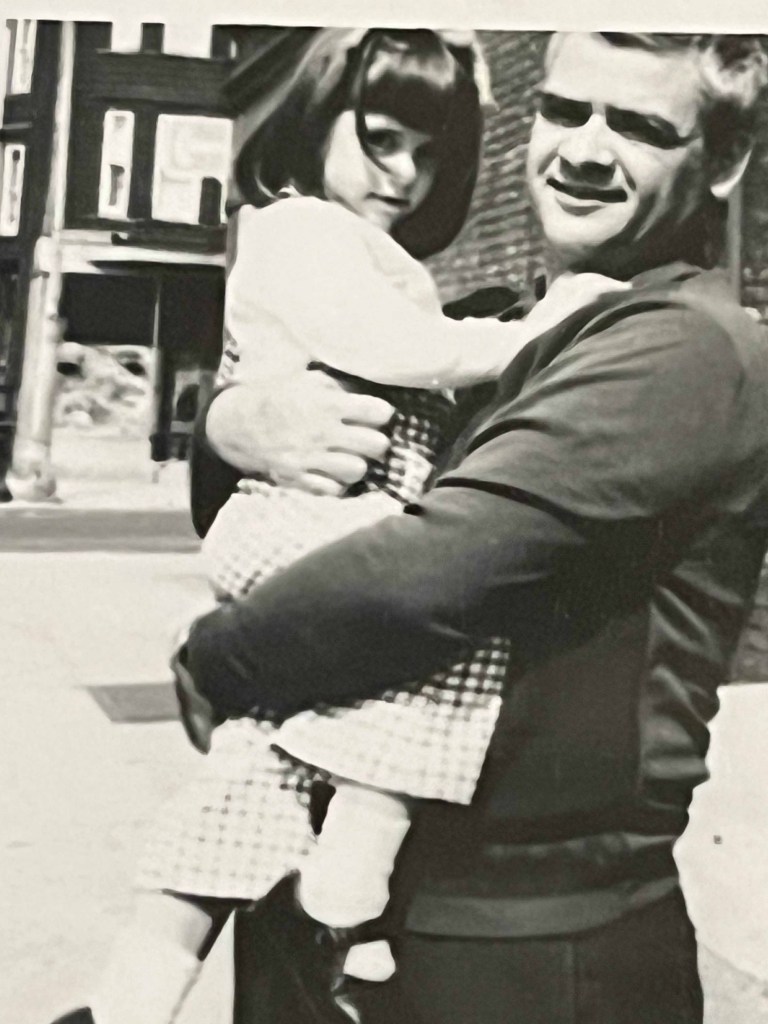

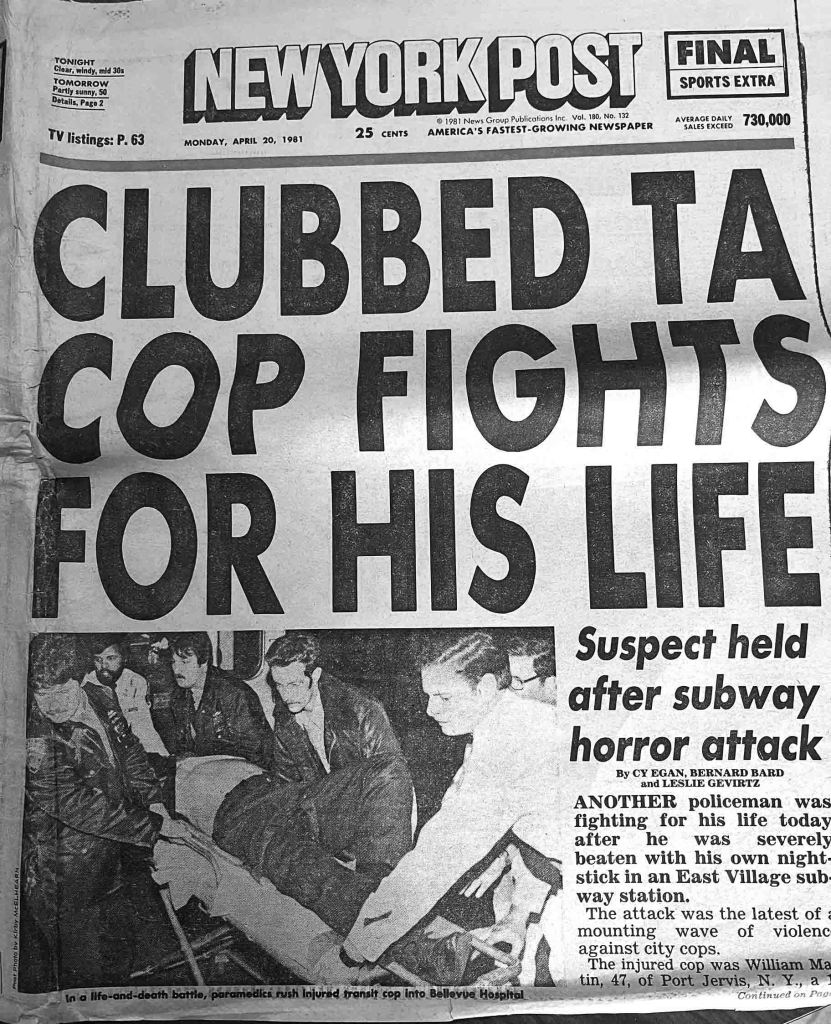

Easter 1981, NYC Transit Police Officer William Martin enjoyed dinner with his family. Then he left for work. He did live,” his daughter Kathleen said, “but it was like he actually died that day. I mean, it was never the same, never the same.”

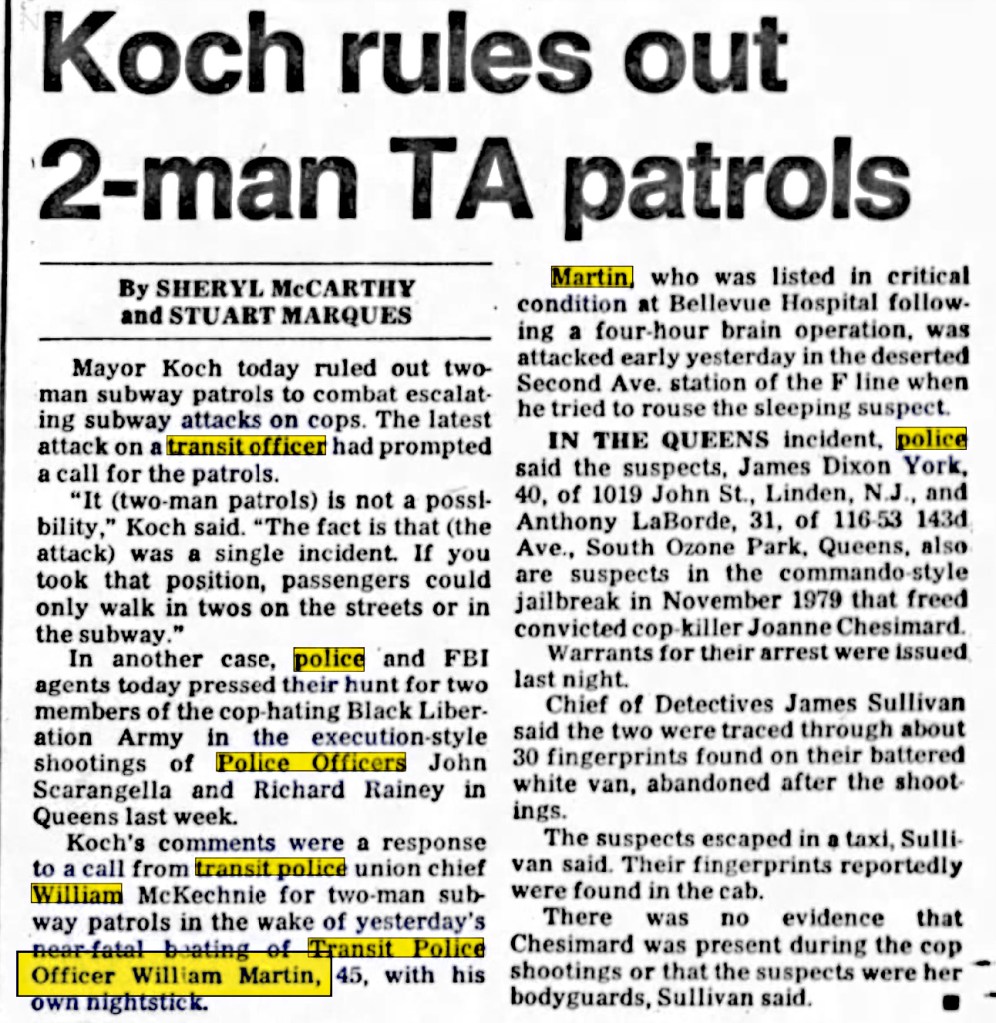

Mar. 6,1970, Ptl. William Martin attended the funeral for NYC Transit Ptl. Michael Melchiona; Officer Martin took these photos:

I stood with thousands of other officers under the Flushing el, in front of Woodside’s St. Sebastian’s Church.

Ptl. Martin was shocked, as were we all that day, about P.O. Melchiona’s killing. William was especially struck that Officer Melchiona was killed in the act of such routine patrol.

Eleven years later, William Martin, too, would face the insidious menace of “routine patrol.”

Police Officer Martin moved from Greenpoint, Brooklyn, to Port Jervis NY. because he was a family man. It was a ninety-mile trip to work. But extended family, like grandma, lived there; his sons, who were in high school, would be in better schools. Life would be better for all.

But one day, it wasn’t.

Sometimes, William stayed in the city with other relatives, sometimes in his camping van. When his boss, Capt. Harry Hassler, heard of his sleeping in a vehicle, he let him sleep in the District office. I worked with Harry, an incredibly empathetic human being.

I spoke with William Martin’s son, Richard, and daughter, Kathleen. They were respectively twenty-four and fourteen on the worst day of their family’s life.

It was Easter, but their dad slept late and didn’t attend church as usual on Easter. Kathleen said he was sluggish. But they had a nice dinner at his son Richard’s home. Kathleen said, “My mother and brother tried to convince him,” to call in sick. But he said he couldn’t. She said, “We all kept saying, come on, stay home, and he said, ‘No, I can’t.'”

This was a man of dedication and character of steel

He left for work.

Transit cops are like minesweepers of the subways. They patrol in repeated sweeps for us. They look for disorderly youths, farebeats, and health code violators. But they also watch for those who would steal from us or harm us. They look to help us when we are ill, injured, or emotionally disturbed. Officers would get radio calls for “an EDP, (Emotionally Disturbed Person)” at a station and respond. They’d try to quiet him, get him help.

William Martin worked at Transit Police District 4 in lower Manhattan. When he got to work, someone had called in sick, so he was given a different assignment. His post was now 2nd Ave station on the F line.

At about 3:00 a.m., Kathleen was startled to hear knocks on the door and the repeated ringing of the doorbell. It was the local police. When police knock on doors, it is seldom good news for those inside. I know; I knocked on doors.

Kathleen said, “They told us something happened to my father, but they wouldn’t tell us what.”

According to reports and interviews of the Martins, at about 2:25 a.m., at 2nd Ave., P.O. Martin came upon a sleeping male on a platform bench. It was just routine, an action he had taken hundreds of times before. All Transit cops did it countless times. But encounters like this are really never routine.

The procedure was: if the male was intoxicated, he’d be escorted to the street to sober up. It was called an ejection. Officer Martin would write on the Ejection card, “Ejected, for his own safety and the safety of others.” If not obviously intoxicated, the male would be told not to sleep and move on his way. Routine.

William was just three years from retirement. But unknown to Officer Martin, this male was a human mine adrift in the subway—a mine of explosive psychopathy.

The twenty-eight-year-old male rose and fought with Officer Martin, eventually grabbing his nightstick. Martin had no time to draw his revolver or his two backup guns.

The male struck Martin in his head again and again, crushing shards of skull into his brain. When Martin fell to the platform, the male kicked him repeatedly in the stomach.

When the beating was over, Officer Martin lay still; beside his head, on the subway platform, was brain matter. Martin’s bloodied nightstick was found on the subway tracks.

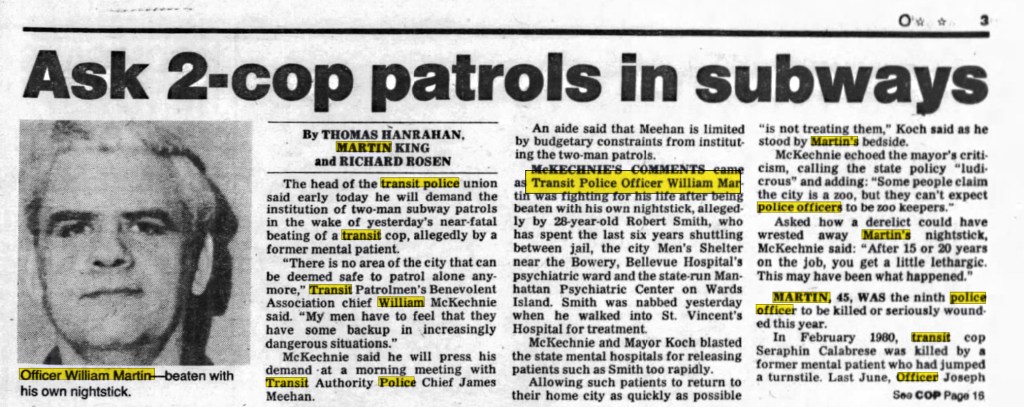

P.O. William Martin was taken to Bellevue Hospital:

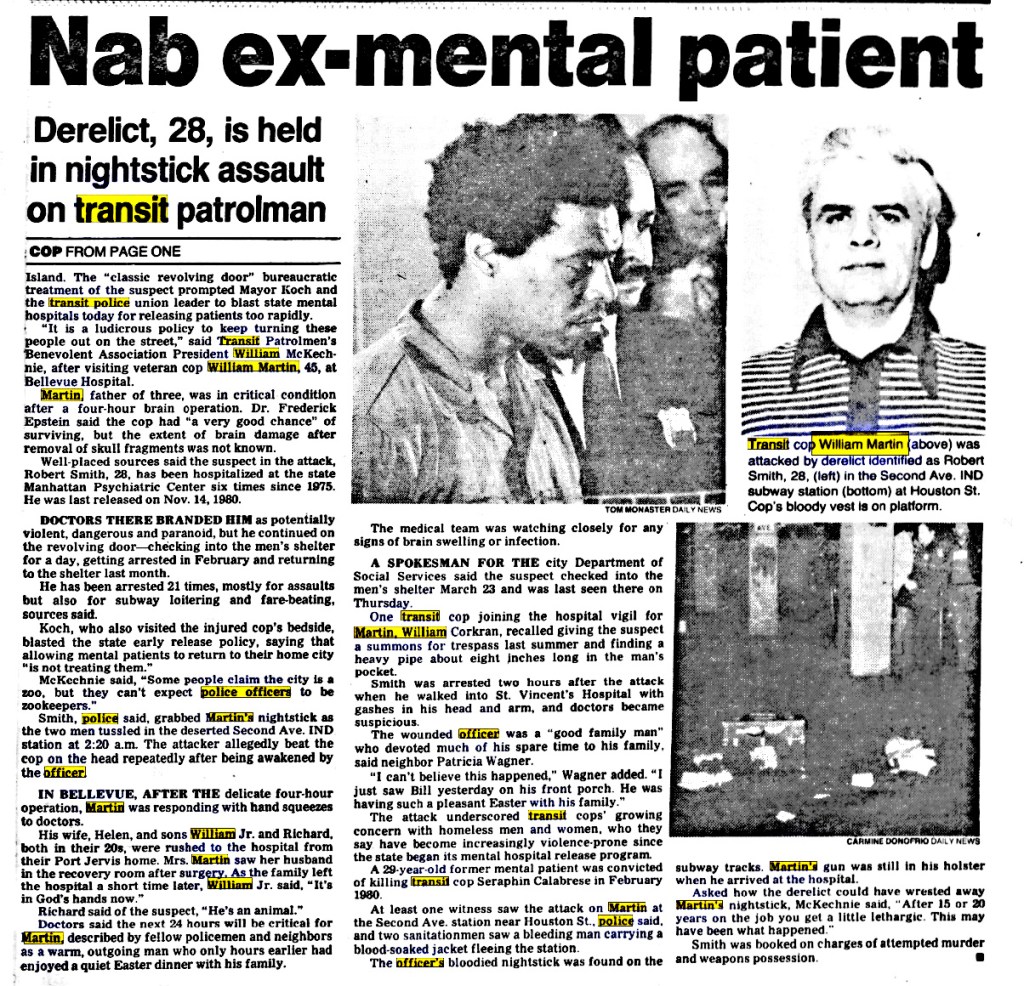

Witnesses saw the man fleeing the station with a blood-soaked jacket. The attacker, Robert Smith, was arrested at St. Vincent’s Hospital, where he had gone for treatment of his own injuries.

NY Times May 12, 1981: “Mr. Smith’s medical records, officials said, chronicle the comings and goings of a man who was hostile and explosive.”

Richard Martin, William’s son, said, “This guy attacked other people and they knew what he was like. They just keep releasing them and releasing them and releasing them.”

The overwhelming majority of people with mental illness are non-violent—but some are. Those with a history of violence need to be on medication. They need to be placed into treatment—for their own safety and the safety of others.

Kendra Webdale was killed when she was pushed in front of a train. Kendra’s Law, enacted in 1999, allows for the forced treatment of violent, mentally ill people. But in Kendra’s case, the pusher had sought treatment.

This link reports: “The man who pushed her in front of a subway had repeatedly sought help. He was discharged from hospitals with little support.” The system failed him – and Webdale – due to a lack of resources, not a lack of forced treatment.”

Of course, the hurdle for effective treatment is money. Effective mental health treatment is essential for all aspects of society, not just subway violence.

It’s always about money.

Including two-man subway patrol:

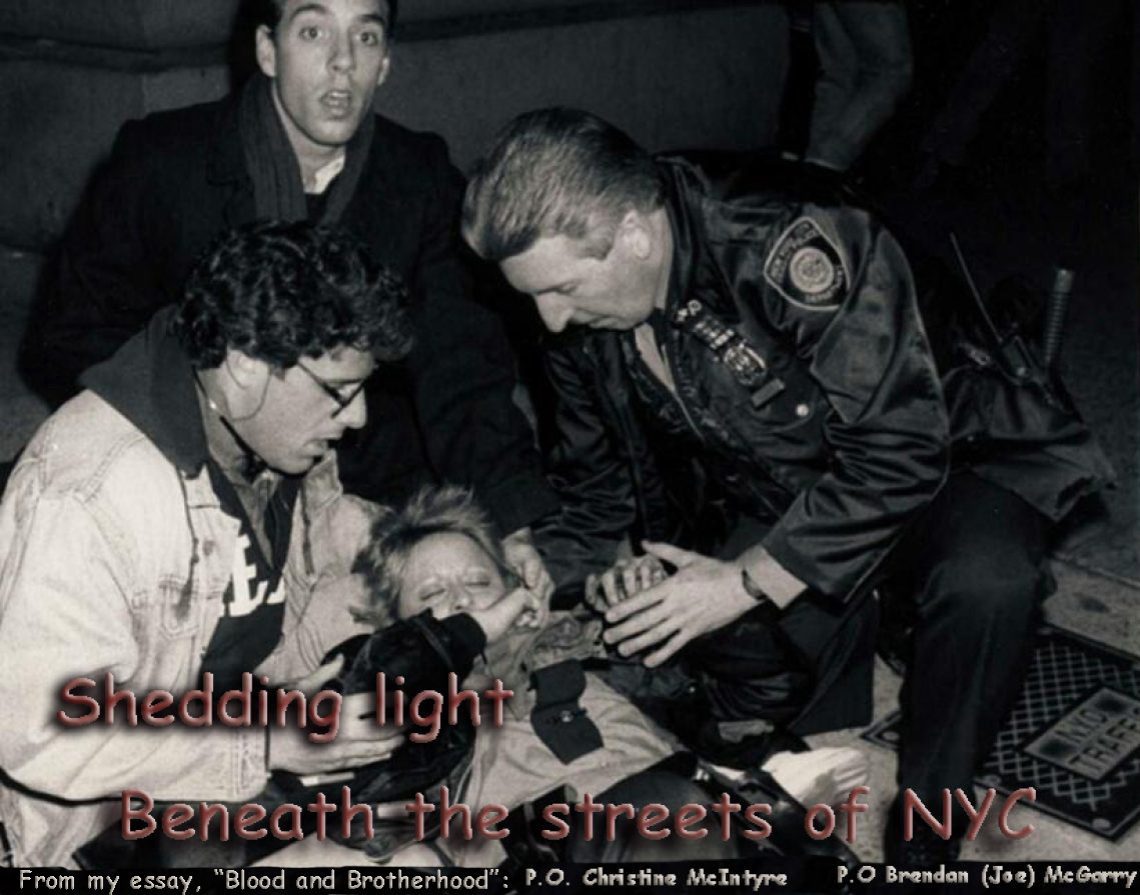

As seen here and in too many other tragedies, one-man subway patrol wasn’t working. Today’s Transit Bureau employs two-man patrol, But it was a long time coming:

The attack was an all-hands-on-deck Martin family emergency.

Kathleen said, “My Mom, me, Richard, my Grandmother, and Uncle Johnny went to Bellevue; Richard drove.” The eldest sibling, Bill, an Army Lieutenant, was flown by the Army to the hospital from Virginia. I didn’t interview Bill; I’m told he’s busy with a full-time job and full-time love and commitment at home.

At Bellevue, the family waited through eight hours of brain surgery. When they did see their dad, Kathleen said, “His head was all blown up like a watermelon. We didn’t even recognize him.” Richard said, “They weren’t sure he would live.”

NYTimes May 12, 1981: Dr. Fred Epstein, a Bellevue neurosurgeon, said that part of the officer’s skull had been smashed and that when he arrived at the hospital for emergency surgery, portions of his brain were exposed.

Some cops have been felled by bullets tearing into them from their own guns. William was felled by bone tearing into his brain by his own nightstick.

William did live. But with severe brain injury. He also had gangrene of the liver from the kicks to his body.

Kathleen said, ‘He was in a coma or semi-coma for six weeks. And when he first woke up it was like he wasn’t really there.” She said, “He was in Bellevue for a whole year. He had swelling in his head. They put a shunt in to drain it, but it didn’t work properly, and they’d have to operate again and again. It took a year for him to learn to walk and talk again.” She said. “He had about twenty operations.”

P.O. Martin had no memory of the incident.

Kathleen said, “Initially, they weren’t going to keep my dad on the payroll.” She said, “But (Transit Police PBA President) John Maye and Brian Flaherty fought for us.” William stayed on the payroll then got a disability pension. Kathleen said, “We were very grateful.”

Kathleen had just turned fourteen and started at Port Jervis Middle School. She said, “I kept my attendance and grades up for them. I didn’t want to cause any more problems for my mother. She had enough to deal with.” Again, I saw steel.

William came home and had twenty-four-hour care for 18 months, then had to go back to Bellevue for another year. Capt. Hassler visited him.

After his second discharge, Kathleen said, “He went to a head injury recovery center. He was there for ten years. From there, he went to assisted living for fifteen years. But at least he was a twenty-minute drive away.

Kathleen said, “He did live. But it was like he actually died that day. I mean, it was never the same, never the same.”

When William was in assisted living his wife, Helen would take him out. Kathleen said, “My mother would have to lift the heavy wheelchair. And I think that she got sick from it.” She said, “She suffered for a good 10 years with very bad back pain.”

In 2002 Helen started to show her first symptoms of Lou Gehrig’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, (ALS).

So many times, I’ve seen pain ignite positive action.

With Dad in assisted living and Mom at home with ALS, Kathleen said, “My husband, Dennis, took care of her. Our two girls, Emily and Jessica, also helped.” Kathleen wanted to help people, so she became a Certified Occupational Therapist. She said, “I can empathize with people because I’ve seen a lot of suffering.” Yes, this is a family of steel courage forged in the furnace of tragedy.

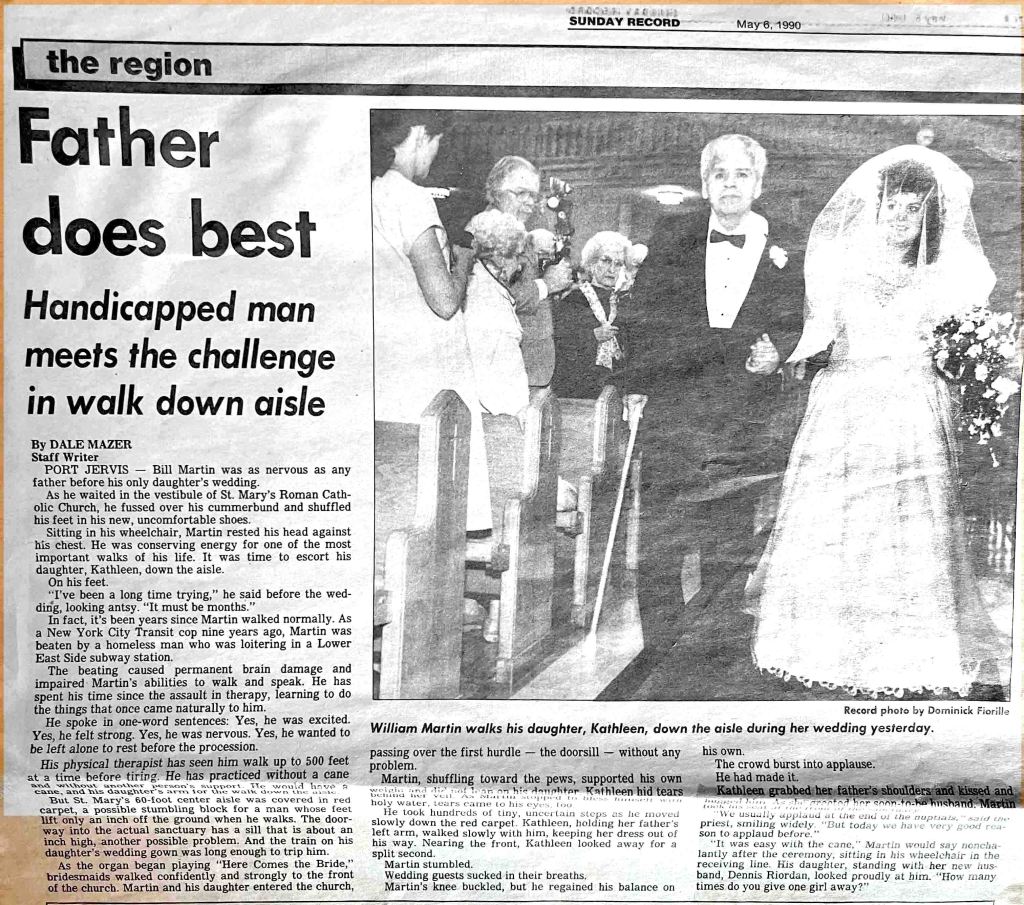

In 1990 Kathleen was to marry Dennis Riordan. William Martin—character undiminished—worked to walk her down the aisle.

In physical therapy, he practiced the walk with the help of staff and his daughter. Kathleen said, “He couldn’t lift his feet well and there was concern he might trip on the carpet that ran down the aisle.” But he did it. He most certainly did it:

Rear: Richard, Kathy, Bill’s wife, Bill, Kathleen, Dennis, Helen, William’s wife, Grandma. Front: Bill’s children, Rebecca and Charlie, flank William.

William Martin intercepted this seemingly innocuous but dangerous man—this live mine. We will never know what would have happened had he not. What passenger would have suffered the explosive wrath of this subway mine—if they had just bumped into him?

- P. O. William Martin is honored throughout the city on memorial plaques

- The Police Academy uses his encounter to demonstrate the dangers of “routine patrol.”

- A K-9 dog, Billy, was named after him.

2006, William’s wife, Helen Martin, died of ALS

William Martin loved his family. He loved photography; he took slide photos at a fallen Brother’s funeral.

But he also enjoyed hunting, fishing, hiking, and camping. He was a Mets and Giants fan; he loved many crafts. He loved Broadway theater, Chinese food, and ice cream.

He loved life.

William spent thirty years in hospitalization, therapy, and assisted living. After three days in hospice, Richard spoke to his father. He said, “It’s okay to let go, Dad. You’ve suffered enough.”

William died on April 9, 2011, when Easter was on the horizon.

William and Helen rest now in well-deserved peace.

Be well,

Lee,

Shedding a little light where the sun don’t shine.

See my sunny side photo essays: Leebythesea

Categories: NYC Transit Police

Thank you for your heartfelt story. Our family appreciates it.

LikeLike

Bill, I was pleased to do so. Your family is an example of fortitude and resilience for others to follow. You are to be commended. Please keep up the good work. Thank you for your service, both military and civilian.

Be well,

Lee

LikeLike